Assistant Professor Catherine Nakalembe

Seeds of Impact: Catherine Nakalembe's Trailblazing Path

From a modest upbringing in a plaster-coated, mud-and-bamboo house in Kampala, Uganda to sharing the million dollar Al Sumait Prize for African Development, Assistant Professor Catherine Nakalembe’s life could easily become a Hollywood movie.

“I sometimes refer to myself as the other 'Queen of Katwe,'” said Nakalembe, mentioning the film about a young girl from the slums of Kampala who became a junior chess champion.

Like the "Queen of Katwe," Nakalembe grew up with limited options, and sports, in her case badminton, offered a purpose and a sense of belonging, defining her early life: “It's like the thing that keeps you busy and keeps you from trouble.” Nakalembe’s whole family was involved with the sport. At some point, she won the junior and women’s championships. One of her sisters is now the president of the Uganda Badminton Association.

Inevitably, Nakalembe wanted to study sports science in college. Yet, her school grades were not high enough for the competitive government scholarship for that course. An alternative that matched her favorite subjects was a new major at the Makerere University: environmental science.

“I think the year that I started [2003] or shortly before , our department got a computer lab and access to GIS software … for me it was kind of striking that there were computers we could use freely during open labs hours,” Nakalembe said, remarking how this encounter with GIS helped paved the way to her career in geographical sciences.

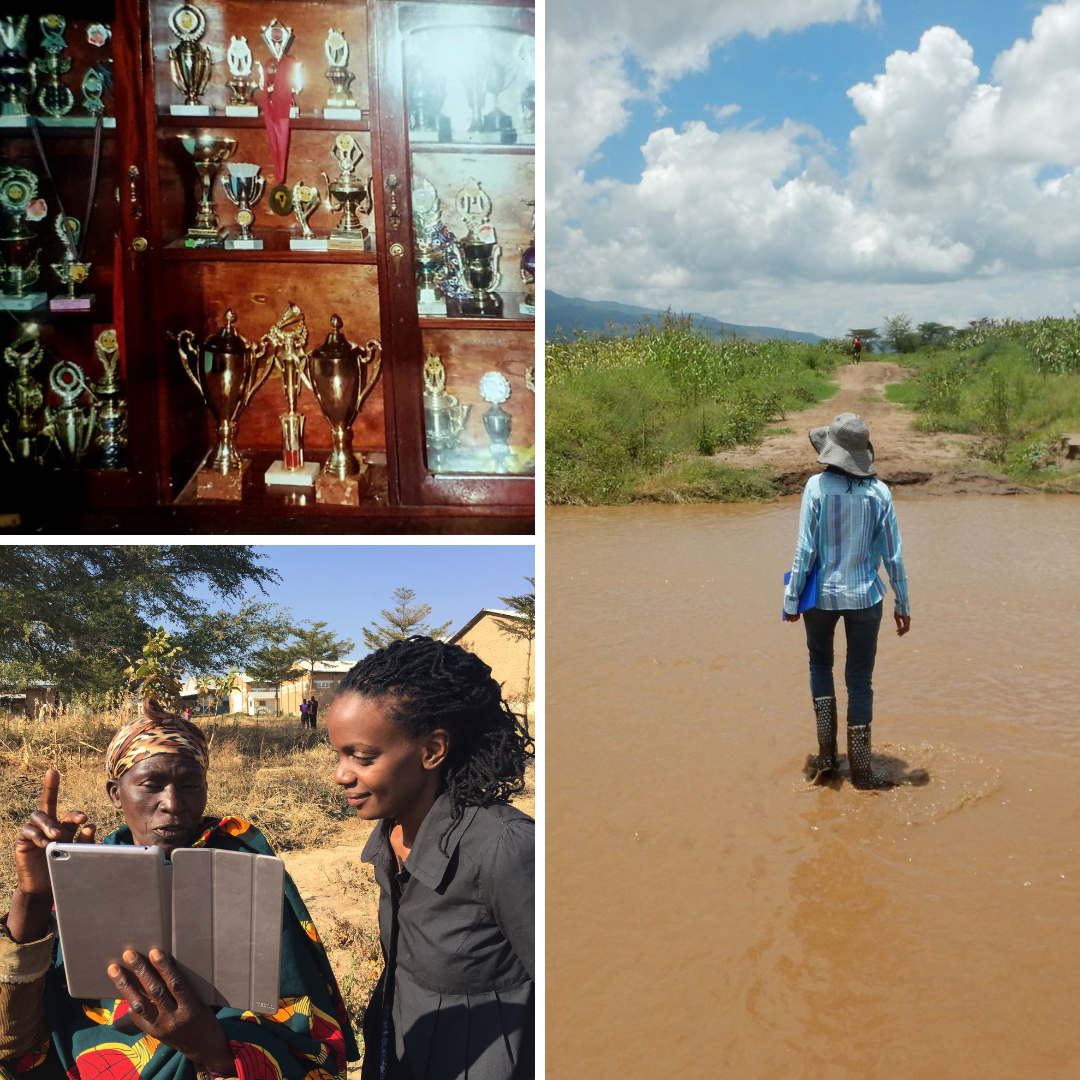

Since Nakalembe had a government scholarship, which gave her accommodation while she chose to stay at home, she was able to use the balance to pay for IT classes. During this time, she learned the foundational skills she needed to work with and fix computers, use GIS software and make maps. For her undergraduate research, she traveled to the east part of the country to map illegal settlements inside a national park.

“It was the first time I used GPS. I have this picture of me during my first fieldwork … walking for days … It was so cold up in the mountains, but I remember this very well because it was awesome,” Nakalembe said enthusiastically.

Against the backdrop of Uganda's unique features, from the tropical forests to mountains and lakes, Nakalembe realized there was so much more to learn and do as a geographer when she completed her undergraduate studies.

“I used to go to the U.S. Embassy, which had an education section where you could go read books for free … It was like walking from here [College Park] to Greenbelt,” said Nakalembe.

In 2007 an education advisor at the Embassy told her about the opportunity to study geography and environmental engineering at Johns Hopkins University. Nakalembe was able to secure a spot there, not without its financial hurdles. She completed her courses in one year and a half to make the most of her 50 (later raised to 75) percent tuition remission while working two jobs: one to pay her food and the other, her rent.

“I passed out at least once because of lack of sleep and going hungry,” she said. “In my family, if you have to choose between eating and school, you choose school.” Her hardworking father, a car mechanic, and mother, who owns a chicken and chips shop, did everything they could to support their children’s education, including applying for loans.

“Too poor to qualify for a higher loan amount she hoped she’d get to cover my tuition, my mom ended up borrowing from all her friends,” Nakalembe said.

Meanwhile, fueling Nakalambe’s ambition was the desire to apply what she was learning to issues back home in Uganda. As soon as she started her Ph.D. program at GEOG, she discovered that she could accomplish what she set out to do.

Through the GEO Global Agricultural Monitoring (GEOGLAM) Initiative, led by Distinguished University Professor Chris Justice, Nakalembe went back to Uganda for fieldwork focusing on food security. “Being in the Department and working with Chris and then within [NASA] Harvest and being a part of NASA SERVIR allowed me to explore and bring my whole self into the problem-solving, grounding, and better contextualizing of our work,” she said. Her goal was to understand why a particular region remained food insecure despite policies and investments.

On one of her trips, Nakalembe visited the Office of the Prime Minister to share her research findings on a severe drought in the northeast of Uganda. “I presented field photographs, videos, and drone footage, emphasizing the widespread nature of the crisis," observed Nakalembe. Impressed, the commissioner encouraged her to write a report for the Prime Minister. The report, presented on Sept. 3, 2015, resulted in swift action, with food aid dispatched two days later.

Nakalembe also recounted her role in advising the Office of the Prime Minister on developing a disaster risk financing program, aligning with her Ph.D. research. Despite initial skepticism from the World Bank team, she asserted her expertise, challenging established plans and advocating for a different approach.

“I was standing in the office … it was me and maybe one other woman and five or six men … and they said: 'We'll go with what Catherine suggests,’” recalled Nakalembe, undoubtedly the expert in the subject.

The subsequent success of the program, particularly the remote sensing component, was based on methods developed as part of her Ph.D. This pivotal moment also set the stage for her continued work in food security and land use across Africa.

Nakalembe’s career might have been a bit different if she hadn’t met amazing individuals such as Olinga John, agricultural extension officer from Moroto, Karamoja whom she spent so much time doing fieldwork, and Marystella Mtalo, who retired from the Ministry of Agriculture in Tanzania, among the extraordinary ladies she works with, and Jane Kioko from Kenya. “They are so committed to their work, and I strive to figure out how my work can continue to support theirs,” she said.

.png)

Plot Twist: The Twins Arrive

One afternoon in 2012, Nakalembe met a postdoc fellow from Germany at the UMD library and spent the rest of the day talking with him. A year later, they were married. A few more years in, amidst fieldwork and many projects, the pregnancy news came.

As soon as she heard the two heartbeats in the ultrasound, she began making plans to turn in her defense and complete her Ph.D. before motherhood.

“I thought the world was going to end after I had my sons,” Nakalembe said. However, the support from her family and the Department, especially the community of fellow mothers at GEOG, helped create a nurturing environment. “I felt I was in a safe place, where I was accommodated, and I could come back to work when I was ready.”

Her determination as a scholar also translated into her determination as a mother. “I was completely absorbed by being a mom; it was such a wonderful time that I had the opportunity to do this,” said the mother who managed to breastfeed twins for a year and a half.

After the babies received their six-month-old shots, Nakalembe was traveling again, bringing them along to fieldwork and conferences. “My husband dropped me off in Italy, then my sister picked me up, then a nanny helped,” she explained.

Juggling motherhood with an impactful career, she found some sort of balance, enabling her work to continue and thrive, but it’s not easy. “Sometimes, I feel like I'm losing hope and faith, getting overwhelmed with too much to do,” she said.

Looking back, Nakalembe reflects on the ripple effects of seemingly small decisions that led to where she is now: NASA Harvest's Africa Lead, an impactful force for food security, multi-award winner in the field of development. There’s so much more she wants to do for Africa, though. The story of the "Other Queen of Katwe" continues.

Main image: Sisters and friends, Young Nakalembe (right) and Norah enjoy quality time together at home in Makindye.

All images courtesy of Nakalembe